Josef Bau: Israel’s Walt Disney and Mapmaker of Hell

The latest in the exhibition series ‘People from Schindler’s List’ at the Schindler Factory focuses on the life and work of artist, animator and reluctant forger Josef Bau.

Born in Krakow, Bau found himself consigned to the Kraków-Płaszów concentration camp in 1941. Press-ganged by the SS as a mapmaker and calligrapher, Bau also put his penmanship to good use forging documents for escapees.

Behind the wire, Bau met and fell in love with Rebecca Tennenbaum. Their secret marriage, strictly against camp rules, is dramatised in Spielberg’s epic Schindler’s List.

It was Bau’s marriage to Tennenbaum that ultimately saved his life – Rebecca was on Schindler’s list, and he was included as her husband, despite the industrialist never having met him.

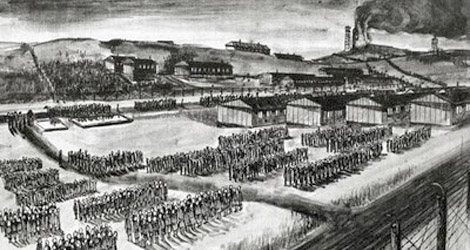

Josef Bau’s sketch of the Kraków-Płaszów concentration camp

After the liberation, Bau finished his studies at the Krakow Academy of Fine Arts, and then emigrated to Israel with his wife and daughter in 1950. It was in Israel that Bau built his reputation as an illustrator and animator.

Labelled the ‘Israeli Walt Disney,’ Bau earned the comparison partly through his indisputable spirit of entrepreneurship. This drive has been inherited by his daughters, Cila and Hadasa, who struggled to keep Bau’s studio functioning and later turned it into a museum.

In 2009 Bau’s sisters launched a campaign to raise funds to prevent his exhibition from being liquidated. The reconstruction of his singular life was larded with additional picaresque when Cila and Hadasa revealed that their father had collaborated with a counterfeiting unit of the Israel intelligence agency Mossad.

In addition to a couple of topographical sketches made of Kraków-Płaszów and the Krakow ghetto as a prisoner, this exhibition of Bau’s work includes several documents penned for his Nazi masters using then fashionable German gothic fonts. Bau later re-asserted his indisputable talent as a scribe through the media of poster design, which allowed him to coalesce text and images on a single surface.

Bau was already a sought-after art designer in the 1970s when Israeli Cinema invited him to design the opening titles for most of its major post-war features. Compared to the style of more acclaimed film title designers such as Saoul Bass, Bau’s sober, black and white compositions contrasted sharply with the light-hearted polychromy of his naïve-style oils on canvas.

Josef Bau’s poster for the film Eskimo Limon (1978)

The curators have also included Bau’s post-war satirical drawings that appeared on Polish magazines before he settled in Tel-Aviv. Cartoons such as the series ‘Germans, Then and Now,’ published in the still active weekly Przekrój, epitomise his personal struggle with forgiveness following his war experiences.

Moral anxiety, or rather preoccupation with moral issues as encountered in his short animated films, has continued as a theme in Israeli animated film, including in the works of Yoni Goodman, who collaborated with Ari Folman on the influential animated documentary Waltz with Bashir (2008).

It is a shame that international interest in Bau has chiefly been focused on his bit part in the Schindler story. Sergei M. Eisenstein once said that Walt Disney’s disruptive imagination had given his country back its lost paradise. This was too much to ask of Bau, who was obliged to map the hell of his nation in his youth.

‘People from Schindler’s list: Josef Bau’ is at the Oskar Schindler’s Factory Museum in Krakow, until October 14th, 2012.