The Krzysztof Olewnik Case: Crimes That Rocked Poland

Kidnap, murder, suicide and police incompetence – Krakow journalist Robert Socha’s overview of a decade of shocks to Poland’s criminal justice system

It was a crime that shocked and enthralled Poland. Top justice officials were forced to resign, and three suspects were found dead in their prison cells.

There has been a parliamentary commission and the prime minister has demanded an explanation, but the crime remains unsolved.

With its bizarre twists and turns, prosecutors have dubbed the Olewnik kidnapping case ‘Twin Peaks,’ after David Lynch’s surrealistic television series.

The story began one October evening in 2001. Włodzimierz Olewnik, a businessman from central Poland, had invited some local police officers to his son’s new house for a barbecue.

They grilled kiełbasa and drank vodka. The party came to an end at about 11pm, when the vodka ran out. “Policemen drink only pure vodka, because coloured alcohol stains uniforms,” one of the officers quipped later.

While the revellers were keeping their uniforms clean, a criminal gang was watching the house from a distance. Once the guests had left, only 25-year-old Krzysztof Olewnik, Włodzimierz’s son, remained at the house.

The gangsters ran into the house, beat Krzysztof, tied him up and kidnapped him. At least this was the official version of the story – until recently.

Ransom

Two days later, the kidnappers demanded 300,000 USD to set Krzysztof free (this was later changed to euro). The Olewnik family were prepared to pay. They thought Krzysztof would be back home and their ordeal over in a few days. They were wrong. It was almost two years before the gang collected the ransom. They then murdered Krzysztof. It was another three years before his body was discovered.

During those two years, the kidnappers repeatedly taunted the Olewnik family. They were extraordinarily brazen, phoning the Olewniks dozens of times and sending letters handwritten by Krzysztof. They warned the family repeatedly not to contact the police, but police were involved from the very beginning. Their phone calls, which featured Krzysztof’s voice speaking about current news stories, were all recorded by police, and their letters were also examined. But no progress was made in finding the Olewnik’s missing son.

Commentators have noted several features of the case that suggest corrupt police officers or other individuals working in the justice system may have been involved in the kidnapping and murder.

In 2004, a forensic psychological statement made to the court hypothesised that police officers could have been involved, noting the extensive use of police jargon and terminology in the letters sent by the kidnappers.

There have also been a series of coincidences that may hint at inside knowledge. In 2004, for example, two police officers left the Olewnik case files unattended in an unmarked police car in the centre of Warsaw. When they returned, the car had disappeared. Neither the car nor the files have been recovered.

It has also been noted that the kidnappers chose to accept the ransom on National Police Day, when an annual ceremony is held to recognise extraordinary acts of bravery or service in the ranks.

The Gang

After years of investigation, the police announced that they had caught the kidnappers. But, apart from the head of the gang, Wojciech Franiewski, they were a bunch of common criminals seemingly ill equipped to have played such games with the police over so many years.

Franiewski refused to speak, except to deny any involvement in the crime. Before he could be brought to trail, he was found hanged and dead in his cell, one morning in June 2007. He was being held in a single cell under what was supposed to be round-the-clock observation. Traces of alcohol and amphetamine were found in his system during an autopsy. The verdict – suicide.

Franiewski’s criminal career had begun years before, during Poland’s era of Communist rule. He was arrested several times for burglary and spent many years in jail. It was apparently an environment that suited him, and he became recognised as a leader among the incarcerated community. In 1991, Franiewski greeted Pope John II on behalf of his fellow prisoners when the pontiff visited the jail where he was being held.

Franiewski may have worked for the feared Służba Bezpieczeństwa, Communist Poland’s secret police service, years earlier. He certainly travelled abroad, both east and west, which was no simple matter for an ordinary citizen under that regime. He must have been a ‘trusted’ man.

Almost a year after Franiewski’s mysterious death, a second member of the kidnap gang was also found hanged in his cell. Sławomir Kościuk, like Franiewski, was also being held in a single cell under round-the-clock supervision. Eight months later, a third kidnapper, Robert Pazik, was also found dead in almost identical circumstances.

The apparent suicides made front-page news in Poland. The justice minister and several top officials in the justice department and prison services were forced to resign. After the third death, Prime Minister Donald Tusk demanded answers.

“I will, of course, expect the prosecution, the internal services, to explain all the circumstances of the third suicide in the Olewnik case. The public is also entitled to full access to all information, so that no dark mystery remains hanging over this issue,” said Tusk.

A parliamentary commission was also called, and found many serious flaws in the investigation.

The Motive

Włodzimierz Olewnik has always said that the kidnapping was not about the ransom. He may be right. Kidnappers are usually keen to take the money and run. Criminologists say kidnappings are commonly resolved in a few days, for better or worse. In the Olewnik case, the hostage was kept alive for almost two years, and then murdered after the ransom had been collected.

Krzysztof Olewnik’s body was found in 2006, on exactly the eve of the fifth anniversary of the kidnapping. He had been buried in a forest, two metres deep, and wrapped in an iron mesh so that his remains would not be unearthed by wild animals. Before his death, Krzysztof spent almost two years chained to a wall in a cellar.

Włodzimierz Olewnik believes that the criminals’ real aim was to take control of his meat factory. He has also revealed that he received several suspicious business proposals a few years prior to the kidnapping, but turned them down when he found evidence of corruption (such as an opportunity to buy a state-owned meat plant for an unbelievable low price).

Some of these proposals, says Olewnik, were made by politicians and a very high-ranking police officer. It was the same officer who supervised the early stages of the investigation in which so many mistakes were made.

The effect of the kidnapping on Olewnik’s company was almost immediate. Banks became suspicious and tried to terminate his credit arrangements, and the company became vulnerable to a hostile takeover.

There have also been suggestions that the case might have been connected to Krzysztof Olewnik’s own business ventures. He was involved in the steel trade, which, according to police, was infiltrated by organised crime at the time.

Krzysztof’s best friend and business partner, Jacek Krupinski, was charged in 2009 with involvement in the kidnapping, but denies any responsibility and is still awaiting trial.

Even wilder theories have been put forward. Could the kidnapping have been part of a bizarre business deal, in which the ‘victim’ was originally being held as collateral with the full understanding of the Olewnik family?

Today, a new team of prosecutors is concentrating on that night more than a decade ago, when the police party and the kidnapping took place. They are still digging at the house, which now lies empty.

A few months ago, investigators once again analysed police footage of the scene, shot in 2001. There were many patches of Krzysztof’s blood, but a few stains interested them in particular.

Ten years after the initial investigation, a new search found traces of DNA in these blood stains that do not match any person involved in the case – neither the known kidnapers nor the family. Something strange happened that night in that house. That night is the key.

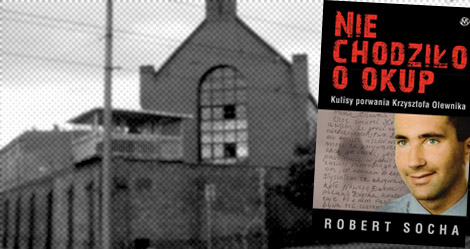

Robert Socha is a Polish journalist working for TVN television. He lives in Krakow. He has written a book Nie chodziło o okup (It Wasn’t About the Ransom) and produced a documentary about the Olewnik case.