Polish Wines – From Zero to Nearly Hero

The urban silhouette of Zielona Góra, around 450 km west of Warsaw, can be discerned through the glass of the Palm House overlooking the city. The glass pavilion full of exotic foliage and fish tanks stands in sharp contrast to the more traditional vines growing all around.

Many Poles are not aware of the strong resurgence of winemaking in their country over the past decade. Productivity is moving on the right track. “In the last decade vineyards have spread all over the country. There are hundreds of amateur plantations and ten official producers who sell their own wine,” explained Roman Myśliwiec, President of the Polish Vine and Wine Institute.

Roman planted his first vines behind his house near Jasło in southeastern Poland in 1982. Since then, he has never stopped expanding his knowledge of viticulture. At that time homemade fruit ‘wines’ and spirits fermented from leftover crops were the pinnacle of Polish oenology.

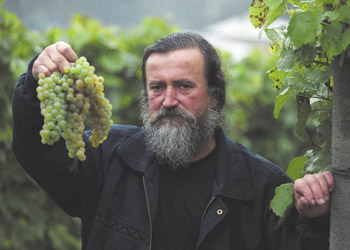

The Golesz Vineyard is set in a valley of the sub-Carpathian plateau, where wine production has been revived in the last two decades. Roman Myśliwiec, known as the ‘Bacchus from Jasło’ led the Polish wine renaissance with around one quarter of the vineyards in the Podkarpacie region. Speaking to Polish daily Rzeczpospolita, Marek Kamiński, president of the local association of winemakers, compared the Polish viticulture scene to that in England in the 1950s when vineyards were mostly run by well-off amateurs as a way of supplementing their incomes on Sundays.

Zielona Góra has a history of wine production stretching back to the 13th century, but the industry suffered two hammer blows in the 20th century. First it lost its workforce to the massive industrialisation of the area at the turn of the century. But it was agricultural policy under the Soviet umbrella that left grapes to wither on the vine in the 1950s that almost ended wine production for good.

The Palm House sits on the site of the Grempler Winery, which was once the most prolific producer of sparkling wine in Germany before 1945. The end of World War II saw the area transferred to Polish control and nationalisation of the industry under Communism. “Several local vineyards are putting their efforts into making sparkling wines, but they are still not yet authorised for sale. Rosé and fortified wines have also lately been in vogue among Polish producers,” said Roman. This strong drive to experiment and diversify underlines the verve of modern Polish winemaking.

Zielona Góra is betting on wine to enhance its image. Last year, the city council commissioned artists to create bronze statues of Bacchus. The city’s mayor, Janusz Kubicki, set an example by financing the first four figures. These small-scale gods of wine have been scattered around the town, in a marketing strategy similar to that adopted by Wrocław with its Orange Alternative-inspired dwarves.

“The harvest has been more than acceptable in terms of quality and quantity this season,” said Robert Andrzejczak of the Talary Winery. Based near Poznań he was in Zielona Góra in September to attend the annual Winobranie Festival. The event has been running for more than 150 years and was conceived to celebrate the harvests of local winemakers in the name of Bacchus.

“During the festival, barrels emerge from every corner of the city and wines are spilled for a token price. Nowadays, beer stalls have mushroomed everywhere, and Winobranie looks more like a ‘piwobranie,’” said Michał, a long-time resident of Zielona Góra who, despite his misgivings, never misses the weeklong event. Winobranie culminates in a parade through the city led by a chubby, bearded Polish Bacchus who dispenses awards to Polish winemakers from the main stage.

Local wines are displayed on octagonal wooden stalls in the market square that are supposed to evoke the shape of the turrets from which winemakers formerly looked down on the city. Ironically, the wines are not for sale and there is no public wine tasting. “If you really want to get a taste of our wines you should pay a visit to our cellar,” explains Krystyna Lewandowska, whose family runs the In the Forest Clearing Vineyard, which arranges tours and degustations in an 18th century cellar.

The reason for this odd state of affairs is that the government has not granted licenses to sell wine since August 2008. Wineries have been organizing private tours to offer samples of their products. This non-profit, underground wine tasting is the only way to bypass the law for small winemakers, which make up the majority of Polish producers. “There is no way to provide festival-goers with a Polish product at an attractive price,” explained a local called Daniel as he poured the festival’s official wine, which was made in Germany, for visitors.

“Relatively high production costs are the problem when it comes to local consumption. We have made various attempts to propose wines representing our region,” explains Maciek, manager of the Winnica Restaurant. Polish wines remain excluded, even from the wine lists of local restaurateurs. “These prices are hard to swallow for our clients,” he adds, displaying a bunch of Polish bottles emptied during tasting sessions.

Since the approval of new wine regulations two years ago, small-scale winemakers producing less than 10,000 litres have not been required to run their own testing laboratories in order to register their businesses. The effects of this deregulation are still to be fully appreciated by local producers. “Our productivity will never be huge. The straight-from-the-cellar sale and limited distribution as a novelty to selected wine shops are the only practicable options for Polish wine,” said Roman Myśliwiec.

An academic interest in winemaking has recently caught on in Poland. Krakow’s Jagiellonian University started its own vineyard in 2005 and Szczecin University is set to follow. The dessert wine produced in Krakow is called Novum and is sold every Thursday at the vineyard. “We harvested some of the grapes on the night of November 11 when the temperature dropped to -8C. This will be the first ice wine produced on our premises,” explained Adam Kiszka, the JU’s vineyard manager.

In August 2011 the Hungarian Foreign Affairs Minister, János Martonyi, and his Polish counterpart, Radosław Sikorski agreed to promote Hungarian wines during Poland’s Presidency of the Council of the EU. Though Hungarian products dominated the scene, the JU’s Novum also made several appearances at high-level meetings held in Poland. “In July we were informed that our wine has been well received at the EU summit for ministers of justice held in Sopot,” added Adam Kiszka.

The University of Agriculture in Krakow is to launch courses in viticulture and oenology in February 2012, giving a boost to the ever-growing culture of winemaking in Central Europe.

Pingback: Bottoms up! The wine museum of Zielona Góra | Inside-Poland.com

Pingback: Poland's first ice wine produced at Kraków's Jagiellonian University | Inside-Poland.com