One of Our Statues is Missing

No other work of its kind can compare to the gothic altarpiece at Krakow’s St Mary’s church, known locally as Mariacki. It is astonishing in its detail and overwhelming in size, a dizzying edifice 13 metres tall and 11 wide. The only way to get to grips with its intricacies is to sit and contemplate them individually.

Yet for 120 years it has been incomplete. Only now have historians confirmed that a statue in a church in the tiny town of Stobierna, in southeast Poland, did in fact begin life as part Krakow’s world famous altar. Professor Piotr Skubiszewski of the University of Warsaw announced last month that the statue was formerly part of the Mariacki altar, following research prompted by the art historian Inga Platowska-Sapetowa.

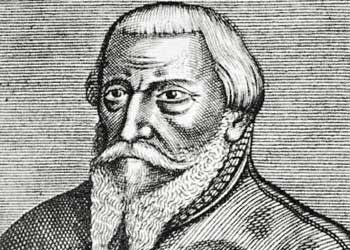

Both Prof Skubiszewski and Ms Platowska-Sapetowa are acknowledged experts on the work of the man who created the Mariacki altar — Veit Stoss, an artist of Bavarian descent whose creations grace not just St Mary’s but other churches in Krakow and his adopted home of Nuremberg. But it was only by luck that his talent was not cut off in its prime, quite literally. Stoss’ artistic bent also lent itself to forgery, and he was once arrested for his part in a fraud that could have cost him his eyes if it had not been for friends in high places who got him off with a mere branding.

Almost nothing is known of Veit Stoss’ (Polish: Wit Stwosz ) early life. Historians are not even sure of the precise year of his birth. Some put it at 1447, others at 1448, while many hedge their bets with the phrase ‘before 1450.’ We do know that he was an apprentice to the Dutch sculptor Nicholas of Leyden, and that he became a master sculptor in 1468. But then, the rank of ‘master sculptor’ was a job title that gave the bearer the authority to win valuable commissions and to take on their own apprentices – it was certainly no guarantee of timeless acclaim or outstanding genius.

Stoss moved from rural southern Germany to the city of Nuremberg in 1473. Although that city was to become his spiritual home, and the place to which he would return and live out his last days, it was in Krakow four years later that he made his name and created his greatest – and most expensive – work.

Stoss and his pupils put the altar together in his workshop at ul. Grodzka 41. As with many great works of the time, it is difficult to say exactly which elements were created by the master, and which by his apprentices. It is easy to forget about the young, idealistic artists and craftsmen, grateful for the opportunity to work on such a grand project under the tutelage of an acknowledged master, whose names will never be known. Great art on this scale was always, at the time, a team effort signed by the foreman. Medieval art was, after all, made for money at the behest of wealthy patrons, rarely by a single artist touched by inspiration and the desire to create art for art’s sake.

In fact, most of the greatest Renaissance artists are known to have taken the role of ‘artistic director’ rather than ‘sole author.’ The British art historian Jerry Brotton illustrates this point with his analysis of Fra Angelico’s Linaiuoli altarpiece in Florence. Brotton suggests that this was in fact a group effort, including carpenters, sculptors and a team of goldsmiths under Lorenzo Ghiberti. Ross King, in his book Michelangelo and the Pope’s Ceiling, also points to the fact that when the artist won the commission to paint the Sistine Chapel, the first thing he did was to hire his creative team.

Whatever the processes involved in creating the Mariacki altarpiece, the result is astonishing in its grandeur. It is made of wood – lime, oak and larch – heavily gilded with gold and featuring around 200 individual carvings. The centrepiece is a representation of the death of the Virgin Mary, her ascension to heaven, and her beatification. This being Poland, St Stanisław gets a look in too, alongside Mary at the moment of her coronation.

The altarpiece consists of three parts, with the outer wings of the triptych hinged to allow them to be opened up to reveal further illustrations, including the Joys of Mary – the Annunciation, the Nativity, the Magi, the Resurrection and Ascension of Christ and the coming of the Holy Spirit. The seventh ‘Joy of Mary’ is her own coronation in heaven, at the top of the altarpiece.

For 450 years, the Veit Stoss altar remained in situ at Mariacki, a source of pride to both Poland as a whole and Krakow in particular (it had cost the town’s merchants the equivalent of one year’s civic budget during its 12 years of construction). So desperate were the Poles to cling on to this treasure, that when the outbreak of war seemed inevitable in 1939, the altar was dismantled and the pieces packed away in crates that were hidden around the country. Their fear was that the invading Germans would steal Stoss’ masterpiece – and they proved justified. Hitler considered Stoss, who spent so much of his life in Nuremberg, to have been a true German. By extension, he saw the Mariacki altar as a German work of art. A special team of German soldiers was detailed to find the pieces and take them ‘home.’ To the dismay of the Poles, every piece was discovered (with the exception of the unknown carving now at Stobierna).

The discovery of the crates containing the altar, stashed in a basement at Nuremberg Castle, prompted one of the fastest post-war repatriations of any work of Polish art. By 1946 the altar was back in Poland – but it would be another 11 years before it was restored to its original and current home in Krakow.

Whether or not Krakow will get its statue back remains to be seen. Certainly, there has been no real drive to bring it from Stobierna to the Mariacki. And, other than for the sake of completion, there is no concrete argument for its removal. After all, according to Inga Platowska-Sapetowa, the sculpture was in effect thrown out as unfashionable clutter when Baroque became the new black in the mid-18th century. Unwanted, it found a home at Stobierna. And perhaps, with proper documentation of its previously unknown provenance, that is where it should stay.

In any case, the altar at St Mary’s draws thousands of visitors each year, and many who make a brief stop in Krakow make the Mariacki their first port of call on the sightseeing trail. From their point of view, one sculpture more or less can hardly make a difference. But what in its essence makes the altar such a draw? After all, such an ostentatious display of gold and glory is so 1480s.

The late Michael Baxandall, a Cardiff-born art historian who specialised in, among other things, limewood carvings such as the Veit Stoss altar, may have touched upon the answer. In his book The Limewood Sculptors of Renaissance Germany, he expanded on his earlier theory of the ‘Period Eye’ – that concepts within works of art such as the Stoss altar are never fixed, but instead depend on the cultural baggage of their own period brought to them by the viewer. Personal background, contemporary fashions and developing ideas can all influence what we see in any particular piece.

Assuming Baxandall was right (and the book won him an international academic prize so there’s no reason not to), his theory of the period eye could explain the timeless appeal of the Veit Stoss altar. It could simply be that people keep coming back, and doubtless will continue to do so, because there is something new in it for every generation. Intriguingly, it could also suggest that there is something beneath the surface that we know instinctively is there, that was significant when Stoss and his team created the altar, but that we simply cannot see right now. But that doesn’t mean we will stop looking for it – and we will be looking for that indefinable something in the vast complexity of the magnificent altar in Krakow, not in a solitary discarded statue in Stobierna.