Shelf Improvement: Flaw

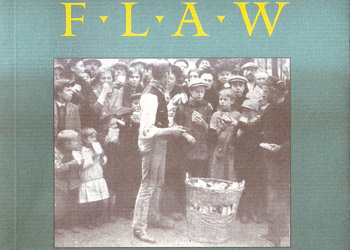

In the spirit of presenting books that aren’t well known, this month I would like to put forward the latest work of Magdalena Tulli, translated into English as Flaw. Published in 2006 in Polish, under the title Skaza, Flaw is an enigmatic book. It takes place in a nameless town, in an undefined time, and none of the characters have names. Instead, all we have are their social functions: notary, maid, wife, student, waiter, newspaper boy. Even the stray dog isn’t a dog, it is referred to as “mongrel”, or its social position in human society. The novel is the unfolding of a single day in this nameless, timeless place, a town that is a sphere unto itself, in which the integrity of that world is suddenly broken by an undefined crisis that leaves a crowd of refugees stuck in the main square. What happens to the refugees, and the reaction of the townsfolk to those refugees is the subject of this book.

The author, Magdalena Tulli, was born in 1955 and first published in 1995 with her book Dreams and Stones. It immediately brought her critical attention, and in 1997 she won the literary award of the Fundacji im. Kościelskich. Her later books, Moving Parts, and In Red also won her nominations for the prestigious NIKE literary prize. Despite her critical success though, she remains outside the Polish literary mainstream. Her novels aren’t novels in the ordinary sense of the word. Her first book, Dreams and Stones, has no characters and no narrative; its rather a lyrical essay on the city. Her later books have narrative, but are splintered and very self aware. Flaw is her first novel that has cohesive narrative running the length of the book, though still with frequent breaks in the story to describe the corrupt, perhaps communist-era workmen who are building the narrative for us, and doing a bad job of it.

Flaw carries within it many references to World War II and the Holocaust. The undefined town is definitely in Central Europe, though it could be anywhere in Central Europe. The time is definitely pre-World War II, and the stock market crash at the beginning of the novel is reminiscent of the great crash of 1929. And the refugees could be Jewish, though it is unclear, and Tulli herself has pointed out that the word Jew is never used in the novel. What she is presenting us is rather a psychological tale of “us” and “them”, the outsider and the local townsfolk, and the fateful human tendency to lose all humanity once those lines have been drawn. She goes through character by character, writing their inner monologues as they self-righteously respond to the humanitarian crisis on the town square. They generally respond in their own self interest, but everyone in a different way, depending on how they are affected or can benefit from the refugees below their windows. Her character portraits are brilliant, and when you read the monologues you can feel that she’s right, that she captured what a person like that would do and think. Though obviously rooted in the historical experience of this region, this is a book that is a universal parable that is still relevant in our times. Bill Johnston’s translation reads beautifully, and recreates the lyrical dreamlike quality of the original text. Highly recommended!