Reflections from the Royal Castle

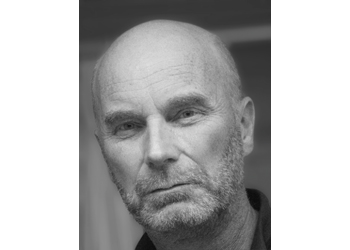

Krakow Post: You have served as the director of Wawel since 1989. Poland has seen vast changes since then. What have been the greatest challenges for you and those working in the field of conservation over the last 20 years?

JO: Well, I would say that everything changed during those 20 years. It was a completely different world. We have to bear in mind that on the one hand, we had to go from communism and the lack of liberty and democracy towards something that we call – rightly or wrongly – capitalism or the market economy, together with a liberal democracy. It was an enormous change. There was change in the legal system, the social system and also in the minds of the people. And it is this last factor that was the most difficult of all. So that was one revolution – a very complicated and very difficult one, both across the whole country as well as here in a large institution of culture.

But as it happened, we underwent another great revolution, not only in Poland, but all over the world – a technological one. Imagine, when I first came to Wawel, there was not a single computer in the museum. So we had to learn how to introduce this mode of technology into our lives and also into the functioning of the museum. At the beginning, this simply involved text processing. Then came the accounting system. And now we do practically everything with computers. The last big change for the time being – we don’t know what might be on the horizon – concerned digital photography. Nowadays, we don’t do practically any traditional photography. And we had to change all of our documentation. Tens of thousands of photographs had to be converted from the traditional technology into the digital one. And we did it. So as you see, there were many levels of change that we faced – I hope with success.

KP: As director of Wawel, you are effectively the guardian of the most fabled historic Polish residence. A dozen or so palaces such as Łancut and Kozłówka have survived in relatively good shape. But thousands of more modest country houses once dotted the Polish countryside. By and large they did not survive the communist era. Do you feel that any can still be salvaged to some degree?

JO: The traditional manor house has practically ceased to exist in this country. There were about 20,000 such residences within Poland’s pre-war borders. As to how many exist today, perhaps several hundred. But another question is what does it mean to exist? It depends on whether we mean solely the architectural structure – the walls and the roof – or the entire decoration and furnishings. If we are searching for examples of living manor houses – maybe ten, maybe 15, across the entire country. And only the smallest ones – those that were not confiscated in 1944-1945, because they were too small to be confiscated.

But you have touched upon a very important problem. And I would like to stress one thing: the disaster for the traditional Polish way of life in the country, with its traditions of the manor house, agriculture and hunting, that disaster started one generation earlier than we normally think – not in 1944-45, but during the First World War, particularly in 1917. The presence of the Polish nobility in the lands of Ukraine, Belarus and Lithuania was absolutely eliminated in the few months that followed the so-called February Revolution in Russia. The worst things happened in the summer and autumn of 1917. Hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of monuments were burnt, robbed and destroyed. Imagine, before 1914, they didn’t even need to close the doors to the manor. There was absolutely no danger. Yet the local people converted into robbers in just a few months. Today, it is almost a desert here in Poland, but when you go there, it is a desert one hundred percent – it is just a desert.

KP: Did you ever experience any kind of prejudice during the communist era on account of your family being members of the nobility?

JO: No, not in my generation, but in that of my parents, yes.

KP: The Wawel citadel has changed its form a good deal over the centuries, not least due to foreign occupation. To the west there is a vast former Austrian military hospital. Much of what lay in between was destroyed after Poland was wiped off the map in the late 18th Century. Do you in any way regret that funds were never available for Wyspianski’s grand architectural plan of renewal?

JO: The present state of Wawel Hill is the result of several centuries of ups ands downs. The worst moment was certainly 100 years ago, when it was full of huge, heavy, ugly military barracks, and it was lacking many of those historical elements that you mentioned. During the restoration works that started in 1905, a lot changed. For example, the most beautiful part of the castle; the galleries of the inner courtyard, were freed, as they had been walled up by the Austrians. Then, just after World War II, two large Austrian buildings were destroyed. We have rather forgotten about that. It was a very quick action by Szyszko-Bohusz, the architect responsible for Wawel Hill. So he freed a lot of space that could then be used to reconstruct some parts of the original fortifications. But of course, it was not possible to reconstruct the destroyed churches and other buildings which once stood in the middle of the lower castle. And we don’t really think about it. It would not be right to do it nowadays.

Coming back to Wyspianski’s idea – thank God he didn’t do it! It was a very interesting design and a very interesting idea, but it would have been a disaster for the historical value of the hill.

KP: Wawel is very much a place of ghosts. Not only royal ghosts. Recently, some of the elements of the Nazi-built Burg were remodelled in a slightly more Polish manner. Working here daily, did you find those lingering spirits oppressive?

JO: First of all, in the context of the western wing of the castle, what the Germans did during the occupation is not necessarily bad. It was a forgotten corner of Wawel which did not have any unifying design. There were four or five parts of old buildings which did not tie together. So as such, it was a good thing that the Germans introduced some order into the Western part of the castle. Probably, if the Polish state had continued its work in the 1940s, the same would have been done by Szyszko-Bohusz – or almost the same. But as it was, they did not finish their work. And we inherited this part of the castle incomplete, and it was not possible to use it. During the 60s, 70s and 80s, the new part of the castle became dilapidated. And we had to choose between restoring the building in the style of the Third Reich – which was not a very pleasant prospect – or adding some corrections. Everything we did was to simplify the design. And now, to those who don’t distinguish between architectural styles, I think it looks quite OK as a historical building. For those who understand what it is, they will I hope see it as a good 20th century interpretation of traditional architecture. Of course, it is not a part of the castle that should focus the attention of tourists. We prefer that they pass quickly through into the inner courtyard.

KP: Are there any major plans for Wawel over the next five years or so?

JO: We are now realising a big project involving the repaving of the external courtyard. Everyone who comes to Wawel sees this and suffers because of it, because we had to close 50 percent of the surface area. But there is also good news, because it is advancing very quickly, and quite soon, the part in front of the Western wing will be reopened – in fact before the Grunwald anniversary. So in two weeks we shall have a large part of the courtyard ready. I am happy to add that this is the first European-financed project on Wawel Hill.

The second part of this interview will accompany the 600th anniversary of The Battle of Grunwald, which falls this month. The exhibition, “The Sign of the Glorious Victory,”opens at Wawel on 15th July.

See also: The Battle of Grunwald: A Vital Victory