Solidarity’s Spiritual Leaders

As the old saying goes, to whom much is given, much is required. That goes for the laity as well as the clergy, especially in Poland. It is true that the men in black robes do enjoy a special status in Poland, but at a time of need some of them were indeed called upon to do the extraordinary tasks required of them. It is also a fact that some ended up paying the highest price for this. The last of this bunch who can, without any exaggeration, be called martyrs died on the threshold of a new dawn, as it were. While the year 2009 was – in Poland and in Central Europe at large – one of generally joyous anniversaries, and rightly so, it was also marked with a few sad ones.

Just as there was nothing cold about the Cold War in many corners of the world (such as Korea, Vietnam or Afghanistan), so the term “bloodless revolution”, which describes the events of 1989, does not take into account the victims who had lain down their lives for the cause of change, sometimes just days before the change took hold.

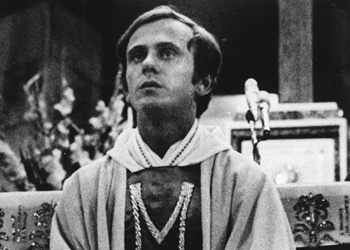

The single most important political killing that took place in Polish modern history was the brutal murder of Father Jerzy Popiełuszko, largely known as the chaplain of Solidarity. The soft-spoken, yet charismatic priest was kidnapped, tortured and killed in October 1984 by operatives of the regime. The gruesome assassination of an ordained man only solidified the status of that icon of the movement in the minds of his supporters.

However, while Father Jerzy remains the most vivid image of the repression by a fanatical system in its dying stage, at least three other high-profile Catholic priests were targeted after his death. Their names were Stefan Niedzielak, Stanisław Suchowolec and Sylwester Zych.

In 1989, Monsignor Niedzielak was in his 70s and had a long record of being a thorn in the paw of the communist government, as a long-time author of patriotic sermons delivered on so-called “forbidden holidays” – the feasts celebrated before the Second World War, but discontinued under communism. But the thing that had gotten the priest in the most trouble was his commemorations of the Soviet wartime massacre of military officers in the Katyń forest. The lawless slaughter of Polish POWs, blamed on the Nazis, was a taboo subject in communist-ruled Poland and could be freely discussed only after the fall of the regime (incidentally, it was only recently that the story found its way to the big screen, in the film by Andrzej Wajda).

Niedzielak, being privy to the details of the gruesome Katyń massacre, recalled the plight of the victims of Soviet oppression, especially those deported and killed inside the Soviet Union in that slaughter as well as others murdered by the Soviets. The visual manifestation of this was establishing the Shrine of the Fallen in the East along with placing symbolic crosses in the Powązki Cemetery in Warsaw (which were systematically destroyed by unknown culprits). The organisational aspect of his activity was his role in establishing a community of relatives of those killed “in the East”, known as Rodzina Katyńska (The Katyń Family). For all this activity the priest received threatening letters, suffered beatings and other forms of harassment (including an attempted kidnapping). The final act of violence came on 20 January 1989, when assailants broke his spine in his private quarters at the parish office. That was followed by a media campaign of misinformation and defamation, aimed at tarnishing the image of the accomplished priest.

Only a few days later, on 30 January 1989, the body of 31-year-old Father Stanisław Suchowolec, a personal friend of the late Father Popiełuszko, and his family’s spiritual guardian, was found in his Białystok apartment, the murder having occurred in the small hours of the same winter day. This time, a campaign of defamation on state-run television had preceded the death, caused by asphyxiation by carbon monoxide, the result of arson.

In the summer of the same year, the third clergyman was killed. Sylwester Zych was found dead at a bus stop in the seaside town of Krynica Morska. Hated by the secret police, the priest had extended his help to a clandestine youth opposition group, and had spent four and a half years in prison in the 1980s.

To this day, it remains a mystery not only who murdered the priests, but exactly what the motives were. There is no clear answer to this question. Perhaps, party hardliners were attempting to sabotage the planned talks between the government and the opposition by sparking social unrest. Public outrage and protests could have derailed the process of negotiation. This theory might explain the first two murders. But the killing of Father Zych clearly must have been about revenge, at least to a degree, as on 11 July 1989 Poland’s political transformation was a foregone conclusion. On the other hand, some suggest that the murders were a way of disciplining the opposition, the “stick” part of a carrot and stick approach exercised by the communist government. If communism on its last legs settled scores by murdering its opponents, was it “clearing the field”? Whatever the motives, when deliberations at the famed Round Table began, a respected senior intellectual initiated them by asking those present to observe a minute of silence to honour the deaths of two murdered priests: Stefan Niedzielak and Stanisław Suchowolec. Since all of the speeches were broadcast with a short delay, state television was able omit that portion of Mr. Siła-Nowicki’s presentation to the viewers. It was perhaps a sad final chapter in keeping with the true nature of those deaths – all under a curtain of silence. That part of the discussion was finally screened on Polish public television in 2009.

Today, it does not cost us anything to remember or, for that matter, not to remember those who fought for freedom, armed only with the power of their conviction. In those old days, it cost a lot. And yet the motto of one of those champions of remembrance, Monsignor Niedzielak, when he struggled against all odds to honour the departed was: “If we forgot them, you, God, forget us…”