Masłowska: No Mincing of Words

You are picked up by the police for intimidating a female staff member at a McDonald’s into giving you a free Coke. At the station, the woman interrogator knows all your answers before you do. Coming down from a major speed trip, you’ve had enough of this hallucination and then she starts explaining that this station does not even exist. Look out the window, she says: you won’t find landscape, weather, not even climate change – it’s all decoration, it’s all written. And then she goes on about her own literary exploits and ambitions. As you storm out of the station, you advise her to write a memoir, I Was a Fuckhead.

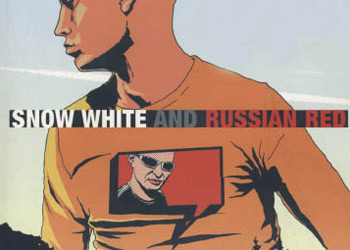

You are Silny (Muscles, in free translation) – a dresiarz, or the tracksuit-clad Polish chav, and the narrator of Wojna polska-ruska pod flaga bialo-czerwona (Snow White and Russian Red), the biggest Polish literary sensation of this millennium. She is Dorota Masłowska, the shy 19-year-old schoolgirl who wrote the book and who has just led you through a charming little scene. It manages to marry post-modernist playfulness and showing up of the literary convention with the Romantic metaphysical horror and showing up of the very world as an illusion (“life is elsewhere”) to deliver a rather neat piece of social criticism. We live in a plastic world, she says, and we think words and thoughts that belong not to us, but to television ads, talk-shows, quizzes. Our culture, our very life, is shown up.

Not the most original of stories to tell about the world we live in, you will say. True, but it is one that will bear any number of tellings so long as they have grace or force – and this book has both. Its secret is in the language – dirty, rumbling, largely oblivious to grammar or logic, vulgar and utterly seductive. When it was published in 2002, The War On Russkies Under the Polish Flag, as the title is perhaps best translated, gave many younger Poles the illusion of hearing their own internal monologue amplified and broadcast to the public. It is impossible to speak quite the way Masłowska’s characters do – but it often seems impossible to think any other way.

Inimitable, her voice became the first of a wave of “Young Polish Writers”, a phenomenon which, as Masłowska’s own publisher recently declared, ended in 2007 with the suicide of Mirek Nahacz, at 23 years of age an established novelist. His death came a year after Masłowska won the Nike Award, Poland’s most prestigious literary award named, incidentally, after the Greek goddess, not the shoes. She was then 23 herself and had beaten a field including the poet Wisława Szymborska, 60 years her senior. Mind you, Szymborska may not have been that bothered, as she’d won the Nobel Prize ten years before.

There is nothing quite so irritating as the young genius, so it is no surprise that Masłowska should have many detractors. And their ranks are bound to grow, as the marketing budget for the recently released film of her début novel suggests she has achieved the sort of material comfort that few writers enjoy and which, for those few, precludes critical acclaim, something she has enjoyed in abundance.

Even more annoying, the film is rather good for a recent Polish production. Directed by Xawery Zulawski, the son of a famous director once married to Sophie Marceau, the film does a decent job of translating the biting social satire that lurks in Masłowska’s exuberant idiom into the language of the screen. Mixing conventions, alluding to Fight Club and The Matrix in a single scene, the film can be fun to watch – and for even die-hard fans of the book, Silny will probably forever have the angered face of Borys Szyc, who fills the screen with his inflated pupils, his moronic smile and the rather impressive muscles he had built for the role.

Sadly, my favourite scene falls somewhat flat. When, in the book, a character tells another that we all live in a film, wear costumes and speak scripted lines, this could be a well-worn cliché, but Masłowska’s grotesque delivery makes it sound fresh and exciting. When, in the film, she appears on the screen to make the point and then proceeds to expose the fiction by knocking over elements of the set – well, it all really is a film. She’s statin’ the bleedin’ obvious, innit?

Snow White and Russian Red can be purchased at Massolit Books, ul. Felicjanek 4.