A Trial of Passion

On 4 June, Poland celebrated the twentieth anniversary of the first partially-free parliamentary elections in the Soviet bloc. The crucial achievement of the bloodless revolution was the lifting of censorship and the guaranteeing of freedom of speech and creative activity. However, the very same day that world leaders celebrated in Krakow this June, another event drew to a close. Ironically, it was the longest trial in Polish legal history concerning artistic freedom.

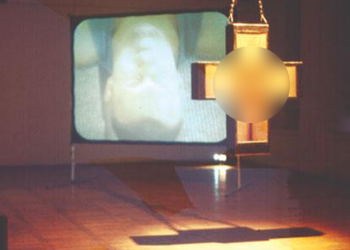

The subject of the litigation was the installation art piece titled The Passion, created by Dorota Nieznalska, an artist from Gdańsk. The work was exhibited at the Wyspa art gallery in Gdańsk at the turn of 2001 and 2002. The piece consisted of an object in the shape of a cross with a photograph of male genitals on it and a video of a man working out at the gym.

In this work, the artist raised the subject of masculinity and carnality in the context of the Polish Catholic tradition, so prevalent in her art. The title refers both to torment and passion and critiques the subculture of bodybuilders, presenting the video of a man who is convinced that he has to train his body in order to attain a certain image of “masculinity”. The exercise is strenuous but he is also doing it with passion.

The installation hung at the Gdańsk gallery for a month, and most likely little would have come of it but for a sensational story in the TVN programme “Fakty”, which created a scandal and was devoid of any factual description of the artist’s work. The matter was then used by a group of activists representing the League of Polish Families together with the Młodzież Wszechpolska (All-Polish Youth, a Polish nationalist youth group) to propagate their own ideology. They based their opinion only on media coverage, without seeing the installation, and filed a complaint with the prosecutor’s office that the artwork was an insult to religious sensibilities.

During the trial Ms. Nieznalska emphasised that the installation did not concern religious issues but was a “criticism of masculinity”. Politicians and activists from the radical political party cultivated the air of scandal by presenting a simplified description of the installation, namely “genitals on the cross”, and depicted the artist herself as a person striving for fame by creating controversy.

The space in front of the courtroom was the scene of various protests, with abusive language directed by the crowd to the artist’s advocates. The issue itself made waves in Poland and Brussels, provoking numerous discussions concerning freedom of artistic expression and the role of the artist and art in society.

During the initial trial in the court of first instance (in 2003), there were no witnesses from the fields of art history, theology or constitutional law, and Ms. Nieznalska was sentenced to six months of unpaid public work and made to cover the costs of the trial. The scandal was harmful for her career, since for a long time other galleries were afraid to exhibit her and indeed other artists’ works that could be seen as controversial. Meanwhile, mayors, deputies and presidents began taking a closer look at what was going in gallery spaces.

In April 2004, the court of second instance reversed the decision and the second case, which began in 2005, finally ended last month in favour of the artist, who was found innocent. This time experts in different fields were heard – a specialist in religious studies claimed that a cross at the gallery is not an object of worship. An art historian mentioned various examples of the presence of the body, sex and religious symbolism used in artistic activities throughout history, explaining that their aim was to take up the theme of carnality, suffering and domination, and was not meant as an insult.

What seemed to be decisive in convincing the tribunal about the artist’s innocence was the entire material from 2001 provided by TVN and presented during the crucial hearing on 13 May 2009, in which Nieznalska explained the meaning of her work, assuring several times that she did not mean to insult believers’ feelings.

“It was not possible to answer the question, whether the offended party would also have felt offended if they had seen the whole installation and had known the artist’s intentions,” reflected the judge, Marcin Kradziecki. However, he remarked that “the artist knew that the combination of a holy symbol with genitals can seem to be offensive.”

According to Izabela Kowalczyk, an art historian, the whole issue resulted from the inaccuracy of Polish law, since paragraph 196 of the Penal Code, which was the basis of the accusation and concerns the protection of objects of worship, is ill-defined and should not be used to judge artistic activity.

The verdict appeared to confirm than an artist has the right to provoke and should not be limited by regulations. The relevant question that emerges is as follows: where are the limits? Is everything permissible in art? Priest Krzysztof Niedałtowski seemed to give a sage answer in this instance: “Artists themselves should mark the borders, taking into consideration their own consciences and respect for others.”