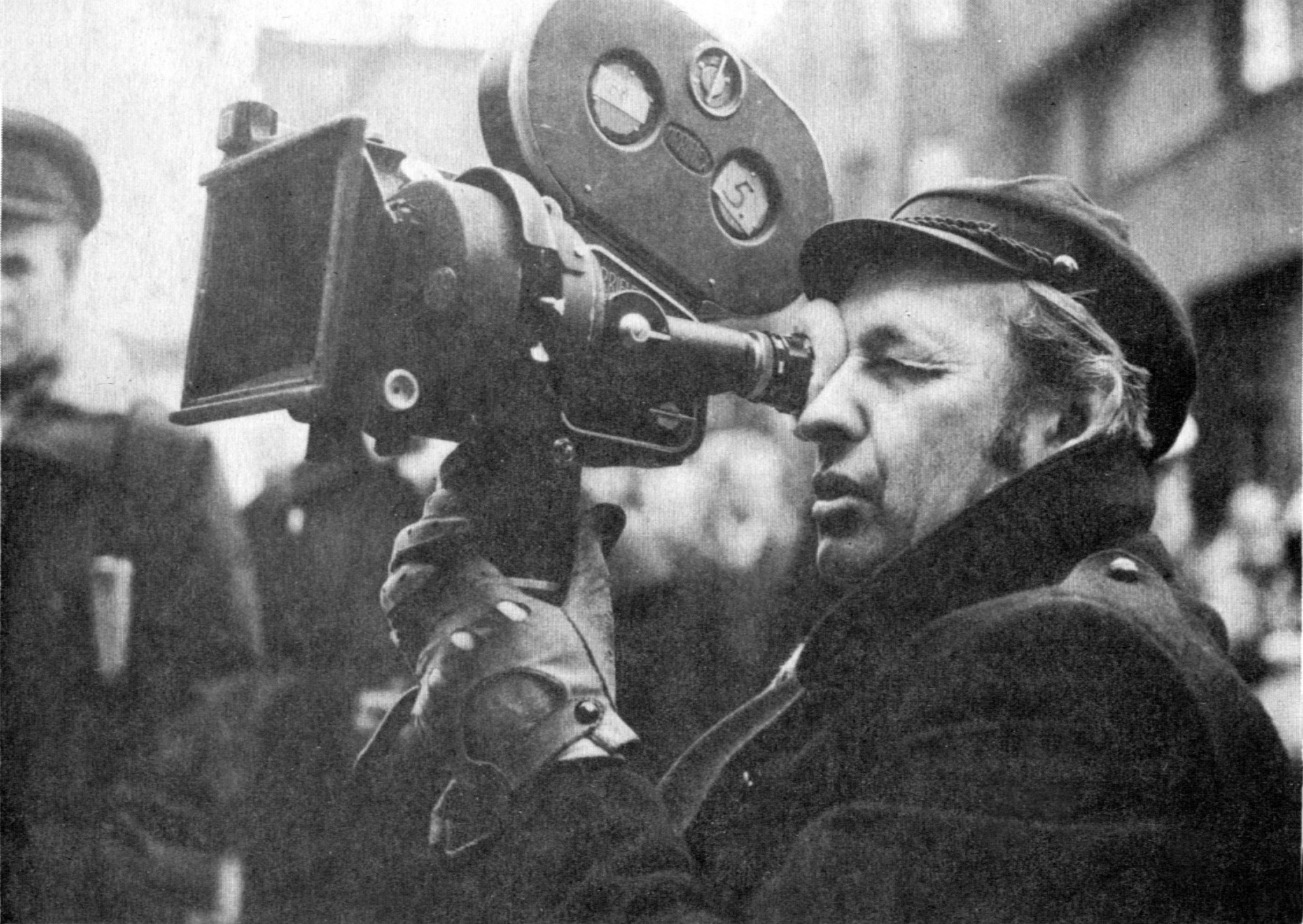

Filmmaker Andrzej Wajda Makes Final Journey

In the aftermath of the Second World War, a cluster of European directors emerged that would redefine the art of cinema. At the funeral of Andrzej Wajda in Krakow on Wednesday, Poland bid farewell to one of the brightest stars in that firmament.

“When I was young I had high hopes that we could change – and better – the world,” Wajda once wrote.

“We believed that people of different countries and different races and different continents would learn to know one another through the art of film, that knowing one another better would make them friends and allies.”

Although he noted the limitations of film in later life, the director’s enthusiasm never left him. He was apparently considering six different movie projects when he died on 9 October aged 90. He had just presented his latest work Afterimage at Poland’s key annual film festival in Gdynia, and he was due to attend the Rome Film Festival this week.

His admirers from across the pond included Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola, and Steven Spielberg (the last was instrumental in ensuring that Wajda was presented with an Oscar for lifetime achievement in 2000).

Yet unlike his colleagues in the West, Wajda was compelled to play a tricky game with a totalitarian regime for much of his career. He resolved not to join the Communist Party. Moreover, he managed to undermine the regime in numerous films, most famously in Man of Marble (1977) and Man of Iron (1981), the latter chronicling the surge of the Solidarity trade union, yet also allegorically with his 1983 film Danton, in which the titular French revolutionary, played by Gerard Depardieu, was widely understood to represent Lech Wałęsa.

Having initially studied painting in Krakow, Wajda made his mark in the fifties with his World War II trilogy. In the latter two works, he made the most of the so-called ‘Thaw’ that followed Stalin’s death, garnering the Special Jury Prize at Cannes in 1957 for the haunting second instalment Kanal, in which Polish insurgents take to the sewers as the doomed Warsaw Uprising against the German occupiers draws to a close. He likewise scooped the Fipresci Prize in Venice in 1959 for its follow-up Ashes and Diamonds, the film that catapulted actor Zbigniew Cybulski, “the Polish James Dean”, to international stardom.

His exploration of Polish identity led him to adapt a number of literary classics, among them Władysław Remont’s The Promised Land (1974), about the Industrial Revolution, and Jarosław Iwaszkiewicz’s The Maids of Wilko (1979), an elegiac work that evoked the lost world of the Polish manor (1979). Both won Oscar nominations. As Wajda himself remarked of the latter, finding a suitable manor house proved a test in itself, given that very few of the surviving ones retained a semblance of authenticity in the wake of the communist land reform of 1944.

Certain projects had to wait until the fall of communism, such as Katyn (2007), the first feature film by any director on the WWII Soviet massacre of Polish officers. It was a deeply personal project for Wajda, whose father had been among the victims. The film gained the director his fourth Oscar nomination. He later realized the 2012 biopic Wałęsa: Man of Hope.

In person, he was down to earth and approachable, invariably brimming with enthusiasm and humour. It was typical of him that he channeled his seemingly boundless energies into supporting a host of cultural causes. When he won Japan’s substantial Kyoto Prize in 1987, rather than building himself a house, he had a sleek museum of Japanese culture constructed in Krakow, the city where he had lived since the war, cooperating with noted Japanese architect Arata Isozaki and Pole Krzysztof Ingarden. When he heard that young Polish artist Piotr Ostrowski had taken it upon himself to save a historic stained glass atelier in the city, he championed the endeavour and helped have a pavilion raised that would showcase some of the enterprise’s works. Several noted film directors emerged under his wing, including Agnieszka Holland and Ryszard Bugajski. He later founded a film school. When young hotshot Jan Komasa followed in Wajda’s footsteps with a movie about the Warsaw Uprising, the older director visited the set and offered his encouragement.

Politically, Wajda aroused the ire of the right in recent years, criticizing the now ruling Law and Justice party, and standing up for Wałęsa, a hate figure in the right-wing press. He opposed the entombment of the late President Lech Kaczynski at national shrine Wawel Cathedral following the 2010 Smolensk plane crash, a matter that bitterly divided – and continues to divide – Poland.

However, the ruling party’s attempts over the last year to label oppositionists as unpatriotic or communist seem on rather shaky ground as regards Wajda and his friends in the arts.

It is as an artist that Wajda will above all be remembered, both in Poland and abroad. Columnists of various political shades noted that while there were hits and misses, he will endure as a towering figure in Polish culture.

There was spontaneous applause from members of the public as the urn containing his ashes was brought out of Kraków’s Dominican Church on Wednesday afternoon. According to the director’s last wishes, he was interred at the picturesque hillside Salwator Cemetery, where several other family members had been laid to rest. He is in good company, joining writer Stanisław Lem, whose work he adapted half a century ago.

The author of this article conducted an interview with Wajda in the autumn of 2007, following the the Polish release of Katyn. The interview, in which the director reflected on a number of themes, was published in the Krakow Post in 2009, when the film went was released in the UK.