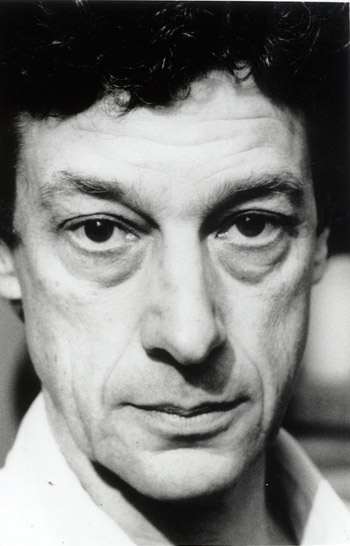

Zamoyski: Reflections on the Bloodless Revolution

KP: In your new book, Poland: A History, you raised the issue that whilst many minor informers had been exposed, some of the communists who had blood on their hands had gotten off scot free. Do you think that more should have been done to purge the state apparatus and public offices of communists?

AZ: The revolution was bloodless, and that is to be celebrated. I don’t think that anybody needed to be shot or hanged. It should always have remained a civilised process – as indeed it was most of the time.

But what I think was a huge mistake was the announcement of the Gruba Kreska [* the declaration that there would be a line drawn under all communist crimes, allowing everyone a fresh start]. Just the fact of announcing it was a blunder. I remember distinctly that in the autumn of ’89, although they were still largely in power, the commies were shitting bricks; they were lying low, paralysed by the sheer strangeness of the situation. They didn’t know which way to jump. And the minute the Gruba Kreska was announced, they suddenly came out from under the beds and their hiding places, and began merrily asset-stripping and accommodating themselves to the new system. That was a tactical mistake, and caused untold damage.

But I think that there’s another thing which is almost more important. And it lies at the root of the divisions that you’ve got at the moment in Poland. It is that two of the country’s largest political parties basically believe in exactly the same thing, but they cannot cooperate because they are nourished by fundamentally different points of view.

One party is psychologically and emotionally descended from the group of communist youth – Michnik, Geremek, Kuron, Mazowiecki, et tutti quanti, who were essentially of the aristocracy, or the ruling class of the communist state. And in a sense, they carried out a palace revolution. They saw that the system wasn’t working and they tried to turn it into a democracy. And they succeeded. But they had never been aware – because they had been brought up in a different world – of what 90 percent of the Polish people had been through. They just didn’t know, because they had no contact.

The other party largely reflects the point of view of that other 90 percent. That other 90 percent suffered both physically and morally, they were the underprivileged – they represent downtrodden Poland: the workers, the peasants as well as the pre-war elites. They came together with the others to carry through the Solidarity revolution and fought shoulder to shoulder with them. But when the dust settled, it became immediately apparent to them that these other guys hadn’t clocked the real situation. Which was indeed true, because the Mazowiecki lot, once they’d got the contractual government, thought: “Right, well now let’s get on with it – this is fine.” And basically – without quite saying it – said to Wałęsa and the others: “Now you go back to work. You’ve done your bit.” Of course it’s not quite as simple as that, but there was a whiff of that about it. And the others said: “Well hang about – the revolution has only been partial.”

Also it behove the Polish government, the new authorities, the new Republic, at some stage in its first couple of years, to at least openly condemn – you didn’t necessarily need to go and find them and drag them in front of a court of law – but actually just to say: “This government and this state – the new Poland – condemns all those who took part in these and these and these activities, and does not wish any of them to occupy high positions.”

You don’t need to carry out great purges, just to say: “These people are persona non grata,” and give them to understand that if they ever try anything or raise their heads they’ll get walloped.

Take the question of pensions [* former communist bigwigs were granted pensions that were several times greater than ordinary citizens]: not even addressing that was an insult, even though it was probably the result of carelessness – carelessness borne of a lack imagination, and a lack of awareness. And this created a huge wound at the heart of the new Poland, and divided people who were basically on the same side. And that’s what we’re seeing at the moment. The PO/PiS thing is ridiculous – they all believe in exactly the same things. And yet, they are divided by just the way they look at very simple things. And I think that is the major problem. And it all goes back to the Gruba Kleska.

This situation is certainly not helped by the ridiculous way in which the IPN [Institute of National Remembrance] has been run, which makes no sense at all. One section of the public, journalists and historians – I mean, who’s a journalist, who’s a historian….? Well, I can turn up and say I want to see a file, anybody who’s doing research can go and dig dirt on people. And yet for people to get access to their own files is really quite difficult, it takes a long time. Yet meanwhile, the dirt is chucked. And they don’t even reveal the whole file. If you’re going to publish a file, then publish the whole thing for everyone to see. You can’t just say that somebody has a file – you’ve got to say what’s in it. And so I think that the IPN is a complete mess, and I don’t think it’s doing any good. I think if anything it’s doing a great deal of harm at the moment.

See also:

Full interview with Adam Zamoyski

1989-2009 anniversary in depth