Joseph Roth: The Legend of the Holy Drinker

Seventy years ago, on May 30th, 1939, a curious cast of mourners made its way to the Thiais Cemetery, southeast of Paris. People of all political colours turned out; emigrants from Vienna, Berlin and Prague, journalists, and a cluster of celebrated artists and writers. Communists met with Austrian monarchists, whilst the ceremony itself was led by a Catholic priest named – nomen est omen – Oesterreicher. This sparked some noises of discomfort from the Eastern Jews, who had come to chant Kaddish.

His final resting place should have been next to Heinrich Heine at Montmartre, but despite Joseph Roth’s glittering reputation as the author of the Habsburgian epic The Radetzky March and his Jewish-themed masterpiece Job, life was hard in exile and his followers simply lacked the money to acquire some space at the more renowned cemetery.

Born in September 1894 in Brody, Eastern Galicia as Moses Joseph Roth, the writer spent a life of almost constant wandering. At the time of his death on May 27th 1939, he had already been in exile for six years, having left Berlin for Paris almost instantly after the Nazis’ seizure of power in January 1933. From the beginning, he possessed a very clear vision of the threat caused by Hitler to Europe, yet he was also convinced that the Nazis would reap the whirlwind that they had sown. In March 1933, in a letter to his friend, the Austrian writer Stefan Zweig – who would himself meet a tragic end in exile – he wrote: “All writers of a certain quality that have stayed behind will face their own literary death. (…) This ‘national renewal’ is leading to the utmost insanity. It is exactly the form, known to psychiatry, of the manic-depressive. This is how these people [the Nazis] are. They will fall, much sooner than is thought.”

In the aftermath of the war, Roth’s reputation began to fade in the West. Indeed, Harvard University actually turned down some of the author’s papers on the grounds that he was simply not a high enough calibre writer. That decision must be a painful source of regret today. For Roth has re-emerged – largely thanks to the recent translations of Michael Hofmann – as one of the towering figures in Central European literature.

“Roth’s masterpiece is one of the greatest novels written in the last century,” proclaimed Allan Massie of The Radetzky March, on the reappearance of the book in 2003. “A vanished voice” had been given “fresh resonance” gushed The Independent. Superlatives were ubiquitous as historians, authors and critics all queued up to pay deference to this “forgotten genius.”

Roth himself was a man of changing faces. As a young journalist, he cultivated thirteen separate identities about his background. One of his favoured tales was that his errant father was no less than a Polish count. Another of his stories was that he had been sired by a high-ranking Austrian officer. At other times, he held that a famed Viennese merchant was his true father. On one occasion he even asked a priest to write a birth certificate stating that he had been born in a town in West Hungary.

In fact, Roth had entered this world in Brody, a border town with the Russian Empire on the northeastern fringe of Galicia. He was raised at the house of his maternal grandparents, who were German-speaking Jews. He never got to know his Jewish father, who fell ill shortly before Roth junior was born. Galicia had been stripped from Poland by the Austrians in the late eighteenth century, but by the time that Joseph Roth appeared, the Poles were by and large running the show again – in return for loyalty to the Habsburg crown.

In Brody, Roth attended one of only two German language high schools in Galicia, the ”Imperial and Royal Crown-Prince-Rudolph-Gymnasium.” He went on to study German literature in the capital of Galicia, Lemberg (Polish: Lwów; Ukrainian: Lviv.) After one semester at the university there – pro forma – he transferred to Vienna where he soon became good friends with Józef Wittlin, future Polish Jewish poet and author of the Nobel-nominated novel Salt of the Earth. Wittlin was also a gifted translator, and he would later render many of Roth’s works into Polish.

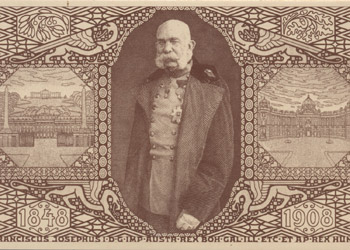

Their studies didn’t last long. With the outbreak of World War I and the death of Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph I in 1916, a world ceased to exist. Both Roth and Wittlin, originally pacifists, were drafted in 1916, and with the outcome of the war – the defeat and dissolution of the Habsburg Empire – they went their separate ways. Wittlin decided to continue his studies in Lwów in the newly re-emerged Polish state, while Roth returned to Vienna.

Thanks to his earlier literary contributions to a couple of Austrian magazines, Roth soon found employment with the Viennese daily Der Neue Tag, where his outstanding talent soon became apparent. Over the next decade, including a three year stint in Berlin, he became one of the foremost and best paid journalists in Germany, his most prestigious employer being the Frankfurter Zeitung.

Roth was sent as a foreign correspondent to cover the Polish-Russian War in 1920. Later, his travels led him to France, the Soviet Union, Albania, Italy and Poland. In 1927, his essay collection The Wandering Jews made its début in print.

As of 1923, Roth began to publish novels as well. His style was fast-paced, lyrical and observant. Many vivid Polish characters would appear in his works, and indeed, he is regarded as the most original chronicler of the former Galician lands. His novel Hotel Savoy (1924) also penetrates the Polish orbit, being set in the industrial city of Łódź – the so-called “Polish Manchester.” The social upheaval of the aftermath of World War I was a rich source of inspiration to Roth. He would return again and again to the themes of the loss of home, social change, and the inability of individuals to find themselves within the turmoil of their time.

Owing to his increasing disappointment with the democratic experience in Germany and Austria, and foreseeing the return to power of nationalist forces, Roth began to look with increasingly nostalgic eyes on the lost Galician world of his childhood. The novels Job (1930) and The Radetzky March (1932) would establish his reputation as one of the supreme chroniclers of the Habsburg Empire.

After 1933, Joseph Roth spent a great deal of time travelling between Paris and Amsterdam, as the latter had become the home of some of the most important publishing houses of German writers in exile. During his last journey through Poland in 1937, having accepted an invitation from the Polish PEN-Club for a series of lectures across the country, he was able to visit his relatives in Lwów for the last time. In 1938 he went to Vienna, shortly before the German annexation of Austria – he was instructed to leave the country. One year later, upon the news of the suicide of his friend the Jewish playwright Ernst Toller in New York on May 23rd, Roth collapsed at the Café Tournon in Paris. He was taken to the “Necker” hospital, where he died on May 27th 1939, just a few months before the outbreak of World War II.

Since the end of World War I, Roth had developed an intense drinking habit. He mostly wrote at cafés and bars, always a glass in front of him. In 1925, he wrote to a friend, ”I’m sick. Drinker’s liver. It’s going to the heart.” Not only was his literary output on a constantly high level (as long as he could get into a café nearby), but so too was his blood alcohol. He needed to drink to be able to write, and to write to be able to drink, as his Eastern Galician friend and biographer Soma Morgenstern once put it.

Next to his drinking habits, his political attitudes had also undergone shifts over time. Finally disappointed with socialism after his travels though the Soviet Union in 1926, he started to embrace the idea of a restored Austrian monarchy after the political takeover of fascism in Europe. Hence his closer contact with Austrian monarchist circles during his last years. Some have called Roth a poet of “Austroslavism,” owing to his longing for a peaceful coexistence of a multitude of nations under the formal roof of monarchy. “I loved the virtues and merits of this fatherland,” he wrote of the Habsburg Empire, “and today, when it is dead and gone, I even love its flaws and shortcomings.”

Another victim of the Nazis. So many who escaped the gas chamber or firing squad paid with loss of their livelihoods, their culture, their worlds.