Jewish Krakow: The Street Art of Kazimierz

The history of Judaism in Poland is a complicated and integral thread woven through the fabric of the country’s identity. For centuries Poland was a place of tolerance for the largest Jewish population in the world until it was nearly destroyed by the Holocaust and subsequent oppression under the communist regime. Today, however, Jewish life is thriving again in Poland, and nowhere is this more evident than in Kazimierz, Krakow’s Jewish Quarter—one of the most vibrant areas of the city. The Krakow Post is pleased to announce a partnership with the Jewish Community Centre of Krakow to bring our readers a new feature, Jewish Krakow, to keep you informed about what’s happening in this important sphere of local life as community members and visitors work toward “building a Jewish future.”

The young and fresh emergence of Jewish culture can be seen through the city’s street art. We explore the significance and creation of two fascinating murals in this installment of Jewish Krakow.

Irene Sendler

Irene Sendler was born in 1910 in Warsaw. Her father was a doctor who treated many patients in a Jewish ghetto in Otwock, Poland. She grew up speaking Yiddish to her friends and was involved in activism against religious persecution as a student at Warsaw University.

In 1939, German authorities banned citizens from assisting the Jewish population, fired Jewish employees, and transferred ownership of Jewish facilities for children and the elderly to the state. Though the creation of the Warsaw ghetto made it difficult to access the community, Irene obtained a pass to allow her to travel in and out of the ghetto and often made more than one trip a day to deliver food, clothing, medicine (most importantly typhoid vaccinations), and money.

Irene was recruited to head the underground Council to Aid Jews, which was credited for protecting children by working with orphanages and welfare agencies to change their identity papers. At risk to their own lives, they also smuggled an estimated eight to ten children out of the ghetto monthly by hiding them in suitcases, packages, and sometimes even coffins. Approximately 2,500 children were saved by efforts of Irene, organizations such as the Council to Aid Jews, and with cooperation of Polish families.

The intention of the Council to Aid Jews was to reunite the children with their parents after the war. The organization kept records of the children’s real names and whereabouts by placing them in jars and burying them in the ground. Irene was arrested by the German army in 1943 after it was discovered she was hiding a list of children’s names, and she was brutally beaten and sentenced to death. She evaded execution by bribing the guards and continued to be involved with activism throughout her life. Her ties to the Home Army, the dominant underground resistance movement in Poland during World War II, was the reason why her story was not celebrated publicly until the fall of communism in 1989. In fact, Yad Vashem, Israel’s official memorial to the victims of the Holocaust, recognized her as a hero, and in 1965 she was awarded with the Righteous Among Nations award. Unfortunately, the Polish government did not allow her to travel to Israel to receive her award until 1983.

One year before her death at the age of 98, Irene Sendler wrote a letter to the Polish Senate saying that “Every child saved with my help and the help of all the wonderful secret messengers, who today are no longer living, is the justification of my experience on this earth, and not a title to glory.”

The mural of Irene Sendler is located in Kazimierz at Dajwor 16 on the wall of the Galicia Museum. This was completed in 2014 as a part of the Galicia’s exhibition of street art in cooperation with the KLAMRA group (BUCKLE Foundation) which is a nationwide initiative that facilitates the creation of several murals in Poland dedicated to the memory of Irene Sendler. The inscription on the mural is a quote by Irene Sendler herself, and reads:

Ludzi należy dzielic na dobrych i złych

Rasa, pochodzenie, religia

Wkyksztalcenie majatek

Nie maja zadnego znaczenia

Tylko to, jakim kto jest człowiekiem

People should be divided into good and bad

Neither race, ethnicity, religion

Education nor wealth

Have any importance

Only who he is at heart

Ephraim Moses Lilien

Ephraim Lilien was a Polish Art Nouveau illustrator and photographer known as the “First Zionist Artist” as he worked with Jewish themes, biblical subjects, and a Zionist context. He was born in 1874 in Galicia and spent much of his life in Israel working with Lithuanian sculptor and artist Boris Schatz to establish the renowned Bezalel Art School in Jerusalem.

He is most known for his portrait of Theodor Herzel, one of the Fathers of Modern Zionism, who was a frequent subject of Lilien’s photography.

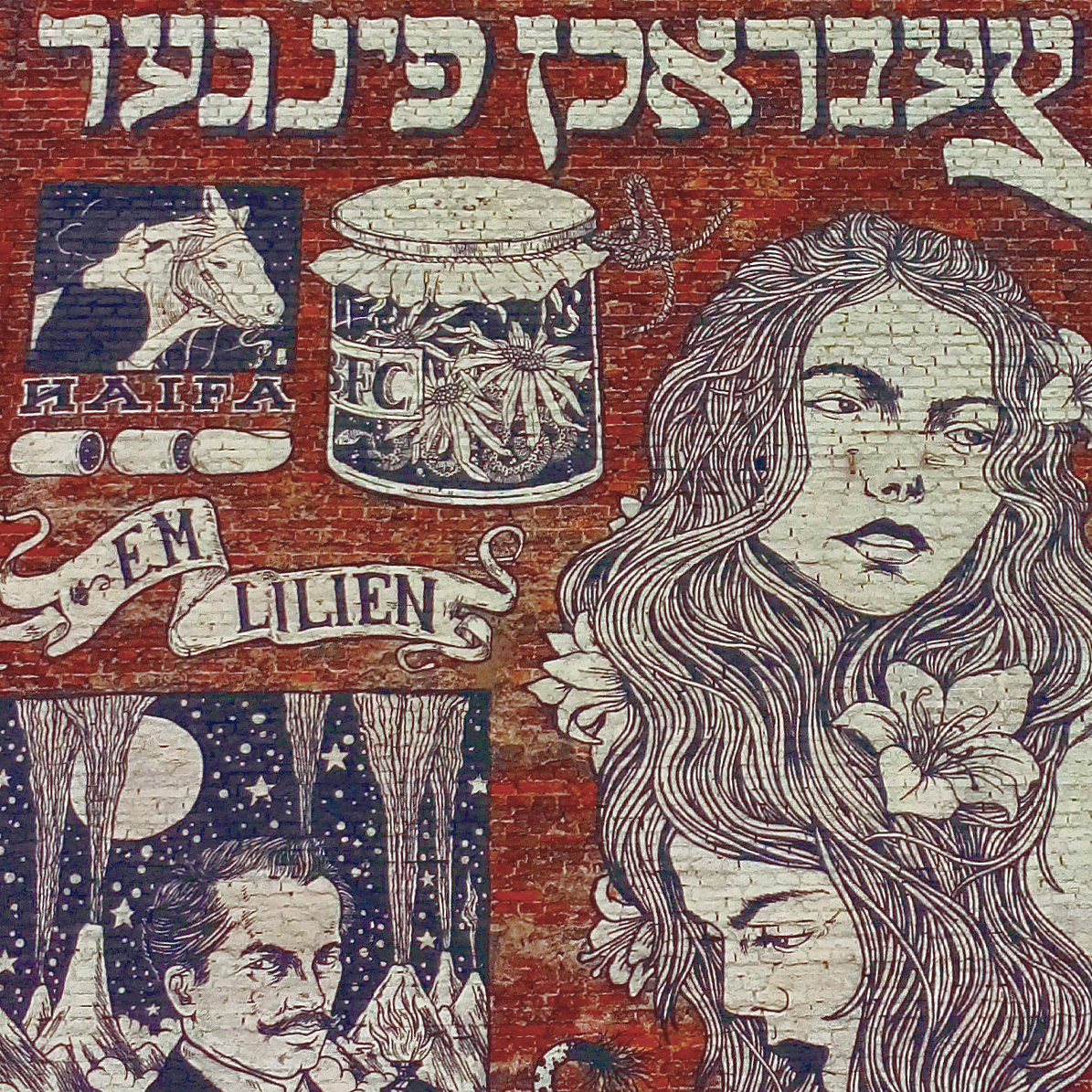

The mural commemorating the work of Ephraim Moses Lilien was created by the Broken Fingaz graffiti crew, which was formed in Israel in 2005. The four-man clan’s work can be seen on the streets of London and Tel Aviv, and they have also published zines and held exhibitions. You can see their symbolic “signature” in the image as broken fingers incorporated into the mural.

Though their work is most known for its psychedelic style, for this mural they found inspiration in the work of other artists such as Renaissance painter Albrecht Durer and symbolist Gustav Klimt. The mural was created during the 24th Jewish Cultural Festival in July 2014 and is located on the “Bosak Building” located at 3 Bawol Square in Kazimierz. This building is named after the Bosak family, a Jewish family that lived in the residence for 400 years until WWII.

These are just two examples of local Krakow street art that celebrate the shared culture and heritage that exists here. It’s an exciting time of renewal that allows Jewish life to thrive from the street up.

If you are interested in learning more about Jewish street art in Krakow, please click here. For more about the Jewish Cultural Centre, you can go to their website.

This article originally appeared in the April 2016 issue of The Krakow Post.

Kazimierz is a good idea! Historical tenement houses, old nick-nack shops, streets full of life… I have been there with seekrakow and really enjoyed it! Jewish culture is so interesting :)